|

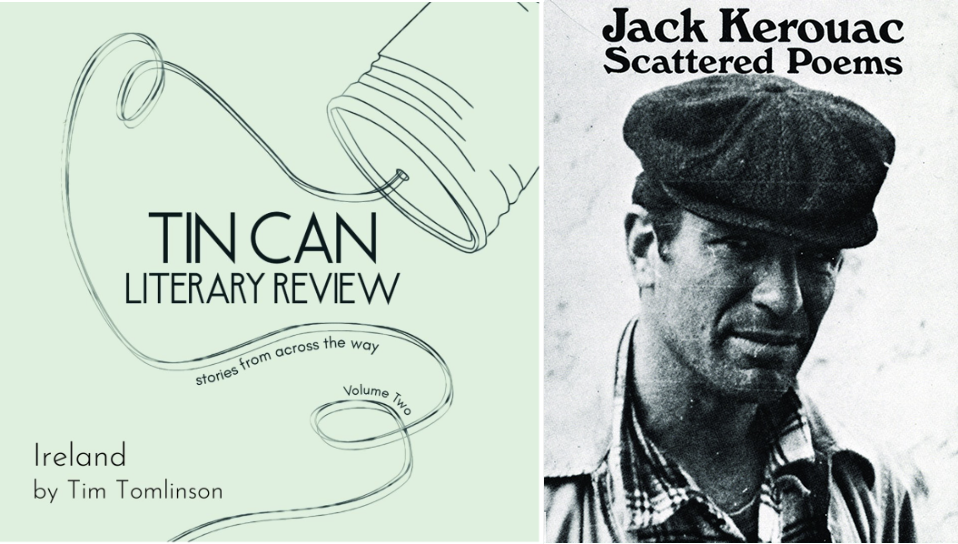

Honored to have a new story in Tin Can Literary Review Vol 2 (reprinted below). There's an accompanying interview here: Haunted Waters Press. Ireland In New York City, a lot can happen in fifteen minutes. But here’s a story about fifteen minutes when what should have happened didn’t. I had this hat, see. A cap, actually. A gray Donegal tweed, kind of a newsboy’s cap I guess you’d call it, made in Ireland, land of the Celtic mystics. Jack Kerouac wore one on the cover of Scattered Poems. Maybe that’s what triggered the dream I had in which I wore one exactly like his. I woke up that morning with a purpose: acquire that hat. But in those years you couldn’t find a decent hat in New York City, you couldn’t find an indecent hat. So I saved up, and borrowed, and borrowed more, and used what I borrowed as collateral to borrow again, until I had enough money to fly to Ireland. I took Aer Lingus to Shannon. The guy seated next to me was Irish. He asked what I planned to do on my visit to his country. I was a bit wary about sharing with anyone that I was visiting their country to get a hat. It seemed at once twee and trivial—twee because the motivation to undertake so costly a journey for something as non-essential as a cap, triggered by a dream, no less, could appear foolishly whimsical, or whimsically foolish, something fucking Donovan might write a song about, and trivial in the sense that the entire sweep of the country’s history, culture, landscape, and people would appear as if it was of little to no interest to me. Joyce, Yeats, Cuchulain, and all I wanted was a cap. But I experienced that want with great urgency. I kept seeing images of Kerouac in his cap—the weathered cheeks, the searching eyes, a supplicant on the byways of spiritual fulfillment, which is how I’d appeared to myself in that dream: a lonesome pilgrim on a soulful mission, but a mission that couldn’t be fulfilled without the proper costume. I had another reason not to share the object of my quest. Given the scarcity of headwear for gentlemen, at least in New York City, I didn’t want to plant an urgent need in anyone else for gray Donegal tweed caps—there might be but a few left, and what if they ran out of my size? So I told my Irish seat-mate that I was visiting his country simply to hitchhike around, have a bit of a look-see, as it were. He said hitchhiking isn’t as easy as you might tink. I said, well, that’s not what I heard. He said, well, begging to differ, but you might, as an alternative, consider the trains. I thanked him for the tip, having neither the intention nor the money to take trains in Ireland or anywhere else for that matter. What else, he wondered, might I have planned? I said I thought I might go up to Belfast. Belfast, he said, why in the world would you visit Belfast? Do you have a side? I said not a side, as such, just an interest, really, a curiosity. He said, well, if I might, let me give you a piece of advice. No one’s interested in being the object of a stranger’s idle curiosity, and if you go up just to gawk at their troubles, they’ll want to know which side you’re on, and they’ll assume you have one because why else even bother entering a war zone, and if you deny having a side they’ll tink you’re a liar or a damn fool, and they’ve already got sufficient numbers of both running around, do you take my meaning? I thought, what am I, on Candid Camera? We hadn’t even reached Nova Scotia and this cocksucker was shooting down my whole trip. I wondered if I could change my seat. I said, take it easy, Paddy. If you want to know the truth, I’m going up to Donegal to get a cap, a gray tweed cap. A cap, he said. That’s about the stupidest ting I’ve ever heard. I said, yeah, I thought so too, but it came to me in a dream, and to me, I told him, dreams have more power than the most perfect equation in quantum physics. So if it’s all the same to you, I said, I’ll go the fuck up to Donegal or any other place I like for whatever goddamn reason. He said, take it easy, sonny, you’re misunderstanding my point. Fuck your point, I told him, and don’t call me sonny. Well, he said, snapping open his Irish Times, and you don’t call me Paddy. We passed Greenland (I think—we flew at night, I was guestimating), and started curving south toward Shannon. We exchanged not another word, landed, took opposite sides on the luggage carousel, and when my bag came, I took it to the exit and went looking for a place to stick out my thumb. Half an hour went by, then another. A total of three cars, each giving me barely a glance. It seemed like the sonofabitch was right. In another half-hour, it started to drizzle. I thought, I’m not spending my visit to Ireland on the shoulder of the road, if you could call what I was standing on a shoulder, and in the goddamn rain to boot. I needed a hostel, or a train. I crossed the road and stuck out my thumb in the other direction, toward Limerick, which was close by. I’d always liked limericks. There was an old man on Aer Lingus, who acted like I was a dingus ... I got that far in under a minute, began working on the interior couplet, when a blue Volkswagen bug from the early 70s geared down and puttered to a stop. It was spooky to see the driver on the same side as me, watching through the sideview mirror. He wore a gray newsboy cap that looked at first glance a lot like the Kerouac cap. Already things were getting mystical. I reached the driver’s door all breathless, the window came down, and it’s the same sonofabitch from my flight. He pointed back behind him and said, “You’re going the wrong way, sonny.” Then he rolled up the window and puttered away. But that’s not the fifteen minutes when something didn’t happen. That came later. First, I made my visit to Donegal, and I got my Donegal cap. I drank a few pints, spent a few nights in a hostel that smelled like dirty feet, forgot about Belfast, and flew home. The fifteen minutes happened when I took the subway downtown to catch a set of Mose Allison at the Bottom Line. I changed for the local at 14th Street, took a seat on a bench and flipped through a Village Voice. A few minutes later the Broadway #1 appeared, I hopped on, and as soon as the doors closed I realized I’d left my Donegal tweed cap on a bench. One stop down on Christopher, I squeezed through the doors, ran up to the street, crossed to the uptown side, and caught the next train north. A fool’s errand, I know. This was New York City. They’d steal the hat right off your head. Leave it on a bench, well, you’re giving it away. Back at 14th Street I didn’t even run. Why bother, what’s gone is gone. But when I arrived on the downtown platform, there it was, on the bench, sitting neatly on top of a folded copy of the Village Voice, which I’d also forgotten. And alongside the cap sat a fetching young woman with a short bob. She wore Thai fisherman pants, Addidas trainers, and a serape. “Anyone forgets a cap like this,” she said, “they come back.” Her name was Terre. She’d recently visited Ireland, too, with her sisters. “What was the purpose of your trip?” I asked her. She said, “The health food.” “The health food?” I said. “And strawberry apricot pie.” I skipped the Mose Allison set. We went for tea in a café with a mezzanine window overlooking Greenwich Avenue. But I didn’t look at Greenwich Avenue, even with all the amazingly cool people passing by. I looked at Terre. We fell in love, or at least I did. I stayed glued to her side for close to two months. She looked so soulful playing guitar with my cap on her head, her fringe pinned to her eyebrows. Then she stopped returning my calls. Typically it took women two weeks to see through me, sometimes three. I credit all extra time to the cap, which I hope she still wears. Getting over Terre wasn’t easy. I spent a lot of time at home behind drawn blinds. If I went out, it was to the Strand where I purchased books I’d add to the stacks of things I’d never read. One day I found a biography of Henry Miller. On the cover he wore a Borsalino fedora.

1 Comment

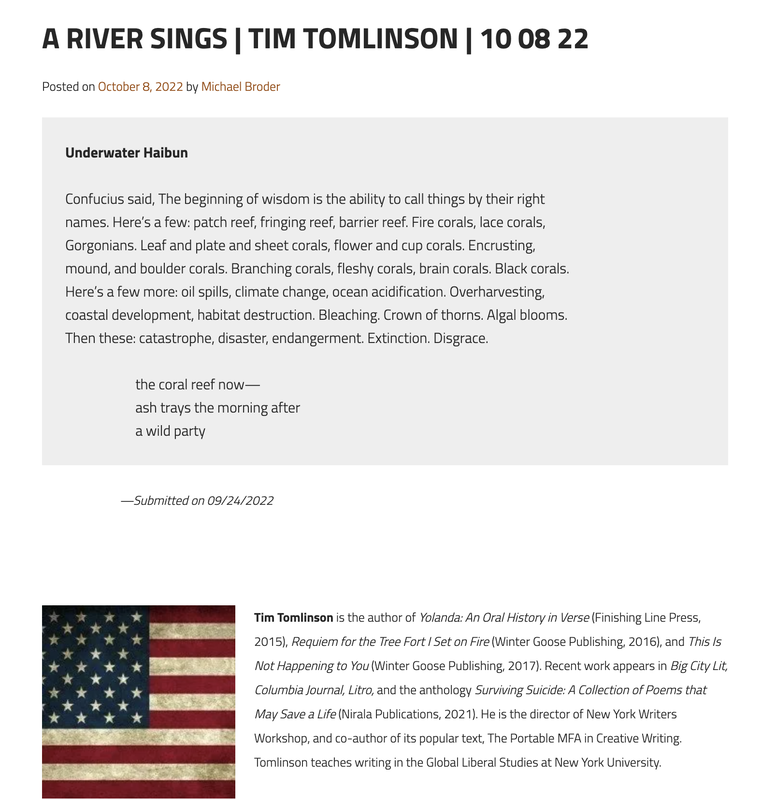

Honored to included on the screens of A River Sings (Indolent Books). Many thanks to editor Michael Broder. This "Underwater Haibun" is from the growing collection, Listening to Fish: meditations from the wet world. (Also from that collection, "Wall Meditations #1.")

Honored to have "The Wall Meditations #1" up on the screens of Lighthouse Weekly. It's from the ms-in-progress, Listening to Fish: meditations from the wet world, an essay-poem-cnf hybrid focused on the perils facing the coral reefs, their populations, and, by extension, everything else. More work from LtF appearing soon. Many thanks to the Lighthosue team, esp editors Caroline and Alice.

On Saturday, Sept 17, New York Writers Workshop launched a new series of readings at the utterly charming Underland Gallery, the vital nerve center of cultural activity in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn (conclusively supplanting Rocky & Nicky's Pizza on Colonial and Bay Ridge Ave.). Featured readers at the inaugural event were Ravi Shankar, Deedle Rodriguez-Tomlinson, and me. It was a night to remember, and to be repeated.

Honored to have this new work, "Blame It On My Youth," appear on the vaunted screens of Jerry Jazz Musician. Many thanks to editor Joe Maita and to the Jerry Jazz team. Thanks to Karrin Allyson for the haunted, deeply inhabited version of the song. And thanks to Oscar Levant/Edward Heyman for writing it.

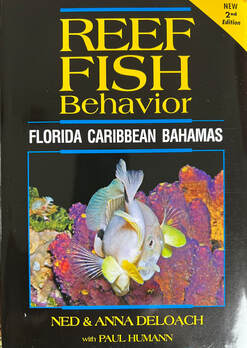

7/18/2022 0 Comments Listening to FishI'm excited to be returning next month to Bonaire, an island I haven't visited in over twenty years. I'll be carrying along my new bible, Ned & Anna DeLoach's Reef Fish Behavior, a companion volume to the great set of fish, coral, and creature identification guides Ned DeLoach put together with the brilliant Paul Humann. There isn't much these people haven't seen, and photographed, underwater. The cover shot of this volume captures Butter Hamlets in a spawning clasp.

Much of the work that went into Reef Fish Behavior was conducted in Bonaire's waters, which have been protected as a marine reserve for over four decades. In that reserve, I'll be doing field work (diving, writing, photographing) for a project long in the works, a hybrid collection of poetry and prose called Listening to Fish. The idea is to listen closely to what fish and corals and reef creatures have to tell us about their imperiled environments. In particular, I'll be thinking about the health of the reefs today compared to what I recall from when I first began diving in the 1970s, when dropping down on a reef was like entering a psychedelic circus. Now, of course, many of the world’s reefs are desolate graveyards. I’m hoping conditions in Bonaire aren’t quite so bleak. And I hope whatever work I do can contribute to the preservation and restoration of what remains. In the new collection, I’ll be including “Night Dive,” which originally appeared in the Tule Review back in 2015 (or thereabouts), and then in my book. I think its octopus will fit right in with the other creature encounters, and I hope I meet some of her grandchildren. Night Dive Once on a moonless night I lost my companions. Their beams were bright but I’d edged over an outcropping into darkness and touched down softly on a rubble ledge where the wall pulsed with half-hidden forms, eyes on the ends of stalks, spiny feelers testing the current, feather dusters vanishing in a blink, spaghetti worms retracting. So sadly familiar-- things I desire withdrawing, their forms disappearing the instant I extend a hand. The reef folding into itself like a fist. Then, from the stacks of plate coral, the arm of an octopus slid, and another, two more, reaching for my fingertips, my palm. The soft sack of the octopus followed, inching nearer, her tentacles assessing the flesh of my wrist, my arm. My heart pounding. Turquoise pink explosions rushing across the octopus’s form. At my armpit, she tucked in, sliding her arms around my neck and shoulder, her skin becoming the blue and yellow of my dive skin. She stayed with me such a short time, her eyes, those narrow slits, heavy with trust, and my breath so calm, so easy. Above, my companions banged on their tanks, summoning me to ascend. How we worry when one slides over a ledge. How urgently we admonish the lost ones to turn back. Honored to have work up at The Antonym: Bridge to Global Literature, and thrilled for another of the Parentheticals series to appear, this one "Parentheticals V: Nothing About Nothing." Many thanks to the editorial team, and especially to Bishnupriya Chowdhuri.

Honored to be included in this Father's Day suite of poems that includes giants like Kwame Dawes and Jacqueline Bishop. Many thanks to editor Ann-Margaret Lim for this opportunity to appear in the Jamaica Gleaner. The photo is of me and Dad, ca 1962, taken in either Queens or Brooklyn.

"Parentheticals VI" now up on Flash Boulevard, a journal I hold in very high esteem, edited by grand flashmaster Francine Witte. I'm honored to join its screens.

4/26/2022 0 Comments Live Encounters, May 2022I was asked by publisher (and photographer) extraordinaire Mark Ulyseas to edit an issue of this very fine literary journal. This is the result (link takes you to my editorial for the issue, from which you can access the rest). I was honored to have been asked, and I'm thrilled by the outcome. Brilliant work by so many--too many to mention, so I'll confine my citations to one contribution, the debut publication of the extraordinarily gifted Rafael Fajer, whose creative nonfiction, Notes from the Borderline, will become one of the critical new additions to the literature of addiction.

Delighted to learn today from an inquisitive student that the title story of my collection is online. It first appeared on the screens of the late, lamented Medulla. Here it is, hosted by Literary Shanghai. I'm honored.

3/17/2022 0 Comments Appearing soon on screens near youLuck of the English-Sicilian (Ethiopian-Coptic), I guess ... I was hoping this would have appeared by today. In its lieu, I'll provide this little teaser.

"I had this hat, see. A cap, actually. A gray Donegal tweed, kind of a newsboy’s cap I guess you’d call it, made in Ireland, land of the Celtic mystics. Jack Kerouac wore one on the cover of Scattered Poems. Maybe that’s what triggered the dream I had in which I wore one exactly like his. I woke up that morning with a purpose: acquire that hat. But in those years you couldn’t find a decent hat in New York City, you couldn’t find an indecent hat. So I saved up, and borrowed, and borrowed more, and used what I borrowed as collateral to borrow again, until I had enough money to fly to Ireland. I took Aer Lingus to Shannon. The guy seated next to me was Irish. He asked what I planned to do on my visit to his country." Delighted to have work in the Winter 2022 Ekphrasis Magazine. Many thanks to editors Michelle Rose Chow, Jay Castro, and H.R. Link. My poems respond to the music of Arnold Schoenberg and Erik Satie. "Six Effects of Schoenberg's Five Piano Pieces, Op. 23" appears on p. 13; "Falsehoods and Banalities in Satie's Trois Gnossiennes" appears on p. 40. The line-up and the work is great and far-ranging. I'm honored to be among so many fine ekphrasticians.

Honored to see "Restless Spirits Depart" appear in The Archer, the excellent international journal out of Bangladesh. Many thanks to editor Masud Uzzaman, and to The Archer team. I wrote the story in honor of my friend, Waray poet Nemesio Baldesco of Samar, who once asked me if I remembered him. Very well indeed, sir. Your work, your spirit, made an indelible impression. (photo Deedle Tomlinson, on a hot morning in Hotel Alejandro, Tacloban)

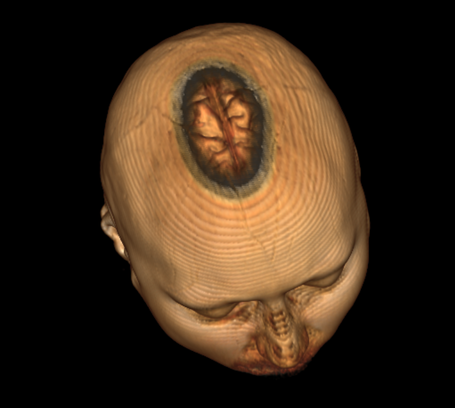

Contributors to SCAN (Science/Art Network) were asked to respond to images in some way connected to the brain, in a Rorschach kind of way. I've always thought that if they opened my brain, they'd find a word cloud of lyrics and lines from movies and plays and fiction. The result: "Opus 23." Many thanks to Paris Lyon, Julia Prendergast, and the SCAN team. It's an honor to have this brain matter looked into.

2/23/2022 0 Comments The Nü Gui at Live EncountersDelighted to have the "The Nü Gui" appear in Live Encounters, March 2022. Many thanks to Mark Ulyseas, the Live Encounters team, and congratulations to all the contributors.

2/16/2022 0 Comments Parentheticals II on Big City LitThrilled to see this one appear: "Parentheticals II" in Big City Lit, Winter 2022. Many thanks to the editors, and congratulations to all the contributors.

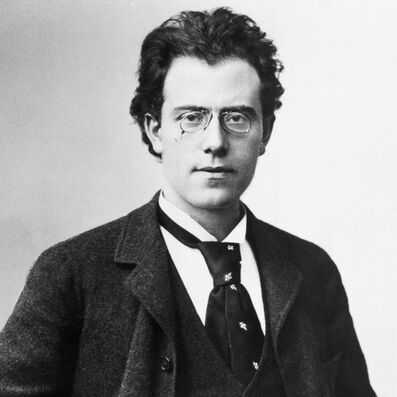

Honored to have "Mahler," a new story, placed with Home Planet News, Issue #9. Many thanks to the editors, and congratulations to all the contributors.

JOHN PERSON, PAUL PERSON, JANE PERSON -- TIM TOMLINSON

(this piece first appeared in the March 2015 issue of Esquire-Philippines) In 2011, 1 took an assignment to teach writing to international students at New York University’s Shanghai campus. I was new to China, didn’t have the language, so what did I plan for our first Shanghai weekend? I checked the film schedule at Alliance Francaise and, to my surprise and delight, discovered that Saturday afternoon’s feature was a screening of Deep End (1971) by Polish-born, London-based director Jerzy Skolimowski. Deep End was one of the rare great 1970s films that had never made it to video or DVD. I’d seen it only once, back in film school in 1979 or 1980, and it left an indelible impression. Set in London (but shot mostly in Munich), it starred Jane Asher, the radiant redhead who was best known as Beatle Paul McCartney’s girlfriend and, for a short time, his fiancée, ca 1964-1968. Jane Asher. For me, no one more fully embodied the beauty, the insouciance, the esprit of the ‘60s girl than she. The ginger fringe, the mini-skirts, the inscrutable green-eyed stare. I developed a hopeless crush the instant she appeared— I was not quite nine-years old— and my heart broke for her when she and Paul split four years later, because how do you get over a Beatle? But another quality that drew me (and, I’m sure. Sir Paul) to Jane was her appearance of complete self-possession. By the time of A Hard Day’s Night (summer, 1964), when the Beatles’ collective persona resolved into distinct musical and public personalities, the question for young identity-seeking hipsters became: Are you a John person (clever, sharp, aggressive) or a Paul person (cute, charming, sensitive)? Jane was with Paul, yes, but she always seemed more a Jane person (smart, sexy, sophisticated) than anything else. Unlike the rest of us, she was not a satellite orbiting Planet Beatle, even if she sometimes appeared in their pictures. The Shanghai screening confirmed this impression. There she was, Jane Asher, big as life, swinging London icon in go-go boots, mini-skirts, micro-minis, bikinis ...then (breath getting short here) topless, and, finally, climactically, heart-stoppingly nude. Fully nude. Swirling-around-in-a-blue-lit-pool nude and oh-my-god was the crush reignited, along with its accompanying heartache. I left the screening with Jane Asher on my mind. I became a Jane person, too. It is widely supposed that Yoko Ono’s influence on John Lennon was significant, perhaps pernicious. Certainly she enabled John to make discoveries—some complicated and unpleasant (the thorny and meandering “Revolution #9”), others stark and revelatory (his first post-Beatles LP, John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band). What influence, I wondered, did Jane Asher have on Paul? The research I undertook to answer that question— biographies, articles, websites, and song after song after song— was thoroughly delightful, if at times poignant, and its answer conclusive: vast, to say the least, and its beneficiaries include not only Paul, but all of us who love music, and who get from music, to paraphrase Greil Marcus, a sense of promise our own lives fail to provide. Remember, Paul and Jane met in 1963, when “she was just seventeen,” and already something of a celebrity herself She interviewed the Beatles for the BBC’s Juke Box Jury programme. John was aggressive and crude (read: insecure and intimidated), and Paul was affable and gallant (read: Paul). Jane was charmed, a relationship was born. It lasted until mid-1968, at which point Paul had become somewhat less than gallant, indeed, (passively) aggressive and, arguably, crude. Jane returned to the London home she shared with Paul, to discover him in their bed with another woman— an American, no less, with the decidedly unmelodious name of Francie Schwartz. In between charmed meeting and traumatic break-up, in the enchantment, the spell, the torment, and the misery of the Jane years, Paul composed some of the most enduring love songs of the 20th century. Consider Paul’s pre-Jane contributions to the genre: “P.S. I Love You,” “Hold Me Tight,” “Love Me Do.” Simple to simplistic, inoffensive to pleasant, lyrically jejune— the musical equivalent of postcards (which, for the record, I love), or e-mails with emojis (which, for the record, I loathe). Then, in less than a year of Jane, we see “All My Loving” with its in medias res opening and its relentlessly urgent pace; “Things We Said Today,” an upbeat love ballad torqued by a minor key; and “And I Love Her,” whose bittersweet tonal ambiguities hint at dark complicated currents just beneath the lyrics’ idealized romance. Would Paul have grown so far so fast without Jane? Quite possible—he’s Sir Paul, one of the rare, the touched, the anointed. But by 1964, John, George, and Ringo had moved into tony London suburbs where, when not on tour (which wasn’t often) they languished in television and marijuana and alcohol. By contrast, Paul remained in London and moved into the attic of Jane’s family home at 57 Wimpole Street. This is where the McCartney learning curve accelerated at warp speed. Without Jane, or someone very like her (and her family), Paul’s growth would certainly not have been as dramatic. How can I make so certain a claim? Because in one year, with Jane, through Jane, or under the influence of Jane, McCartney’s writing evolved from pop generic to personal, complex, and psycho-sociological (all those qualities typically applied to Lennon)—evolved, in short, from pop to art. One of the great dramas of mid-1960s rock songs, that period when rock ‘n’ roll became rock, was the collision between inexperienced working class scruffs, those unwashed lads from the other side of the tracks who didn’t know which side of the plate the fork went on, and their sophisticated and hitherto obscure objects of desire, the daughters of the aristocracy (or what passed for it), with their fashionable clothes and bon vivant behaviors. Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone” and The Rolling Stones’ “19th Nervous Breakdown” are two famous examples in which musically gifted angry young men take their posh intimidating girlfriends down a peg or two. The Beatles contributed their share. Most are attributed to John: “Ticket to Ride,” “Day Tripper,” “Norwegian Wood,” “Girl.” Paul, the story goes, wrote the silly love songs. And no doubt he did— but not when he was with Jane. Jane took him on a roller coaster ride that peaked with rhapsodies (“She’s a Woman”), plunged to tantrums (“I’m Down”), with pleas and put-downs (“You Won’t See Me,” “Drive My Car”) along the way. One reason was Jane’s independence. She gave as good as she got (or nearly). If Paul could pursue his career, as he must, then she would pursue her own (acting). If Paul could take lovers in that pursuit, then Jane could take hers. This is not the posture of a typically submissive Merseyside girlfriend, and young Sir Paul was flummoxed. On Help! (1965), he travels from smitten (“I’ve Just Seen a Face”), to bewildered (“The Night Before”), to vengeful (“Another Girl”). On Rubber Soul, later that same year, he’s beside himself with pain in “You Won’t See Me” (“I just can’t go on/if you won’t see me”), then gleefully derisive in “I’m Looking Through You” (“you were above me/but not today”). “We Can Work It Out,” a Jane-influenced lover’s quarrel, presents one side of the argument: Paul’s. And if this argument is the best he could produce, it’s no wonder she spun him around like a top. What the song shows is that while Paul had his position, Jane resolutely had her own, and she’s wasn’t budging, and she didn’t even have to state it to win. Westminster girls are that slick. If class discrepancy bothered Paul, that didn’t stop him from soaking up whatever culture Jane and the Ashers provided. They played classical music at home and introduced Paul to art with a capital A. Soon he was attending concerts, recitals, gallery openings, collecting art by Magritte, attending plays by Jarry, talking film with Antonioni, and listening to new sounds by Bach, Berio, Ornette Coleman, Sun Ra, and John Cage. Quite a distance from the barber shops and roundabouts of Penny Lane; quite a distance, too, from his band-mates partying in the culturally conventional suburbs. The first masterpiece of this collaboration between Paul and his muse was born in a dream Paul had in the attic bedroom of the Asher home. He woke with a melody in his head, a melody so haunting and complete he was certain that he’d heard it before and unwittingly absorbed it from an earlier source. He tested it on various friends and experts by humming it or playing it on the piano. Where, he wanted to know, had he heard this melody before? And everyone told him the same thing: nowhere. It originated with or through Paul. Doubts of its provenance aside, he began to apply lyrics, which at first failed adequately to serve the melody’s melancholy. Meanwhile, the struggles with Jane persisted. Career obligations pulled them apart, reconciliations (at the Asher family home) brought them together. You get the sense of a young couple in love, but bewildered and exhausted by love’s requirements. You get the sense of a young couple who could not work it out. And in that fatigue, the young couple went off for a short holiday in Spain. On the drive from the airport to the resort, with Jane asleep on his shoulder, Paul’s mood carried him to a simpler past, and the lyrics he’d been searching for finally arrived. 'Yesterday/all my troubles seemed so far away...” The resulting record is chamber music, a string quartet with guitar accompaniment, and Paul’s voice milking the deeply sad, perfectly simple lyrics. It was as if the spirit of Franz Schubert had visited him. By 1966, things were getting wiggier—the hair longer, the skirts shorter, the bellbottoms bellier. The Beatles responded with Revolver, which essayed new forms (Lennon’s droning tape-looped “Tomorrow Never Knows,” Harrison’s Indian-inflected “Love You To”), but it’s the Paul/Jane drama that takes central stage where it drives Paul to higher highs and deeper lows. “Good Day Sunshine,” “Here, There, and Everywhere,” “Got to Get You into My Life”: these celebrate love’s excitement and delicious intimacy. But their flipsides, one deriving directly from the Jane agonies, the other from their cauldron, might each qualify for saddest song of all time. “For No One,” a waltz, depicts the forlorn lover as something less than a footnote to the woman who’s left him so far behind (“You stay home/she goes out/she says that long ago she knew someone/but now he’s gone/she doesn’t need him”). It’s that “long ago” that does it: how is it possible that the securities of love can vanish so quickly, so conclusively? That’s a question I remember asking on the corner of 7th Avenue and West 10th Street watching my former girlfriend walk away with friends laughing, probably, I thought, about me. And when I turned away that night and entered the Christopher Street subway, I joined all the lonely people that Paul wonders about in “Eleanor Rigby,” his other 1966 masterpiece. In “Eleanor Rigby” Paul’s pain elevates to vision; he transcends himself and addresses the human condition. The string quartet of “Yesterday” is doubled, John and George add their voices to the chorus, and a set of lyrics indebted to the emotional tutelage of Jane Asher begins to find its way into anthologies of poetry taught in universities. The relationship’s closing number might be its least memorable but it’s appropriately bi-polar, 1967’s neo-psychedelic bauble “Hello, Goodbye.” In another two years, marked by infidelities, increasing drug use, trips to India, and Jane is out of the picture. Paul’s musical imagination turned away from romantic strife toward others’ stories (“She’s Leaving Home,” “The Fool on the Hill,” “Rocky Raccoon”). The silly love songs spring up (“I Will,” “Oh Darling”) and become, in the post-Beatles ‘70s, something of a manifesto. And Jane? One of the great things about the Paul-Jane relationship is its principals’ categorical moratorium on providing fodder for the gossip mill. The silence suggests deep, mutual respect, which leads me to suspect similar depths in the lyrics of the songs. Jane’s career carried on, with high, sustained achievements in television, film, stage, and later as an author, television personality, and activist. Thinking about her while walking around the streets of Shanghai returned me to one of the moods that animated my adolescence, and I found that melancholy oddly comforting, like reconnecting with an old friend. I want to thank Jane for sticking up for herself, and for causing Paul so much educational pain. I suspect Sir Paul has already thanked her. These images are separated by twelve or thirteen years. The one on the left is from our kitchen floor during a glorious year in Florence, the one on the right is from the living room floor of our current digs in Brooklyn. I hope what I've lost in flexibility and hair I've gained in kindness and stillness. Writing, travel, yoga, and Deedle have been the constants. I think of the final paragraph of Henry Miller's Tropic of Cancer: “The sun is setting. I feel this river flowing through me—its past, its ancient soil, the changing climate. The hills gently girdle it about: its course is fixed.”

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed