|

12/22/2021 0 Comments Books of 2021 (and yesteryear)These are always difficult lists for me to compile since most of my reading dives into the past. That said, I still get around to some new releases and this year’s list references a few. Here’s my picks: The 1619 Project, Nikole Hannah Jones Easy to understand why this one rattles the IWSCPs (imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchs—thank you, bell hooks). It doesn’t just shake the buildings, it shakes the tectonic plates. Hold on—the bumpy ride is just beginning. Afterparties, Anthony Veasna So Stories from a brilliant young writer whose passing just weeks before publication is one of the year’s greatest losses Who They Was, Gabriel Krauze Hybrid tales from the London estates in Kilburn, rife with intoxicating slang, frightening with implications. Last Evenings on Earth, Roberto Bolaño You enter this world, you stay in this world. You even come to like it, but why you’ll never know. Craft in the Real World, Matthew Salesses An unpacking of the creative writing workshop that, like the Nikole Hannah Jones above, shakes the tectonic plates. A provocative, important book for workshop leaders, participants, and institutions. Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror, Carlos Basualdo and Scott Rothkopf This catalogue, for the concurrent retrospective exhibitions of Johns’s vast output at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art, gathers essays that range from historical, art historical, and speculative, from curators, art historians, and literary writers the likes of Terrance Hayes and Colm Tobin. Johns said, do something to an object, then do something else. Not a bad place to start for writers. The Copenhagen Trilogy, Tove Ditlevsen A riveting account of literary ambition forged out of cultural and economic deprivation. Ditvelsen’s work set me off on a memoir kick. These three grabbed me. How I Became Hettie Jones, Hettie Jones Memoirs of a Beatnik, Diane di Prima Feelings are Facts, Yvonne Rainer The Jones and the di Prima depict a long lost New York City (the New York City I love, but missed, like the proverbial wave). So does the Rainer. The first two, like the Ditlevsen, concern aspiring writers, the third a dancer-filmmaker. Sex is also very much on the minds of these memoirists. Gore Vidal said that in the 1950s only three Americans were fucking: himself, Tennessee Williams, and JFK, and that left all the women to Jack. The accounts of these three women suggest something else. In each case, the fucking of the 50s leads the way to the more and merrier 60s. Correctional, Ravi Shankar And while I’m on memoirs, this. Shankar provides a detailed account of his family’s migration from India to the US, and his trajectory from celebrated poet/editor and professor to inmate of the Hartford Correctional Center, the Connecticut prison that forms some of the book’s most riveting scenes. Another important book that explores the 1619 turf of America’s “justice” system. Oblivion, Robin Hemley In this wildly and hilariously inventive posthumous autobiography by an author very much alive, Hemley explores both family history and the career misery of the mid-list writer. With a Kafka quest that echoes Flaubert’s Parrot. Riverrun, Danton Remoto Remoto's brilliant hybrid memoir-fiction-recipe book reissued here in the US, where, in the next few decades, we might be seeing our own bildungsromans of life under a dictatorship. And three current releases in poetry: Post-Mortem, Heather Altfeld In “The Apoacalypse Club,” Altfeld writes, “Let’s face it, the end of days titillates …” The collection supports the claim. Love and Other Poems, Alex Dimitrov A collection firmly ensconced in New York City, and in the New York School circa now. Earthly Delights, Troy Jollimore With a sense of humor part Coen Brothers, part Slavoj Zizek, the poet-philosopher takes on the movies, and existence.

0 Comments

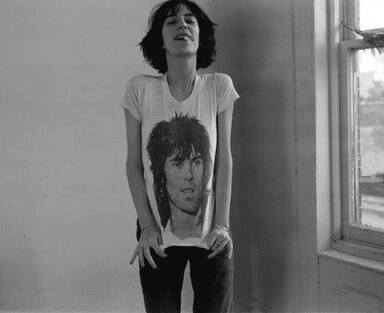

12/18/2021 2 Comments Patti Celebrates KeithSTORYSUNDAY / Litro Magazine

PATTI SMITH TAKES A PISSby Tim Tomlinson / •April 11, 2021 It’s a hellish hot night in New York City’s Central Park. You’re crowded into a concert space, the sun setting, the crowd sweating, the album of the summer, the Rolling Stones’ Some Girls (do-do-doo-do, do-de-do, do-do-doo-do, do-de-do) blasting over the PA system. Track after track you’re wondering when the hell Patti Smith is gonna come on and start the show, at the same time you’re thinking, this is the show. The Stones never sounded this good. This loud. This significant. Love and hope and sex and dreams, Mick Jagger sings, does it matter? And here she comes bouncing onto the stage. Black boots, black trousers, black jacket, sleeves rolled up, arms above her head, bouncing and twirling. She gyrates center stage, grabs the mike—“this town,” she shouts, “is all that matters.” And the crowd roars. Then she’s into the show: “I don’t fuck much with the past,” she snarls, “but I fuck plenty with the future.” There’s a clarinet leaning near her bank of amps and a couple of numbers in, she picks it up and starts blowing. Just noise—squeaks, skwonks, squoinks, no relation to what the band’s doing, no relation to song, to harmony, melody, rhythm, and she’s transfixed like a kid on the spectrum. Blowing, screeking, honking. At the edge of stage right, a roadie lifts a sheet of opaque plastic and holds it neck high. She hands off the clarinet, drops behind the plastic and, for the length of time it might take to let loose a good piss she’s just a dark blur in a deep crouch, like a form underwater. Back standing, she buckles her belt, retrieves the clarinet, and the roadie drops the plastic. You’re thinking, did she just piss on-fucking-stage? Did she piss in public? Piss on the hallowed space? You’re thinking “Piss Factory,” that odor rising roses and ammonia. What was she saying, you wonder. There had to be a metaphor, a message. Piss. Performance. Perversion. Subversion. Your girlfriend says, “You don’t even know if she actually pissed.” “What else could she have done behind that plastic?” “Uh, just about every single thing in the world that’s not pissing?” But you’re not buying it, you insist that she pissed, that you all saw Patti Smith pissing. “Whatever,” your girlfriend says, “but you’re never gonna know for sure unless you ask her, and even then…” ••• You feel indebted to Patti Smith. Only a year back you were a sophomore in college, directionless, the veteran of a lot of dead ends and bad mistakes. Detours and detoxes. You’d pissed on stages, as it were, every single one, without the benefit of a plastic curtain. You were beginning to see a way out into the straight world, a way to become a civilian, to participate, to contribute, to wear the pinstripes and carry the briefcase. You visited your folks, told your mother you think it’s going to be law school for you, then maybe politics. She was so relieved, so happy, she started crying, gave you a twenty to go have a beer in town. Handed you the keys to her Volvo. You hit the back roads, put on the FM. From the top pocket of your vest, you fished what you’d sworn would be your final joint, Hawaiian sins, no seeds, all female. You fire up and pedal down and you’re racing along Sound Avenue. You’d know its curves and dips blindfolded and you race it on autopilot, holding deep inhalations, frenching the exhales. On the radio, a program featuring the new noise out of New York: Ramones, the Dolls, Dead Boys, the Contortions. Out of a bludgeoning feedback maelstrom emerges Patti Smith doing The Who’s “My Generation.” Well I don’t need that fuckin’ shit, she shrieks, the hairs on your neck and arms spring up. You envision your law degree on fire and standing over it, Patti Smith pissing gasoline. ••• The afternoon following the concert with clarinet, you’re in the Caffé Dante where Patti Smith sits in the window scribbling figures into an unlined notebook. She’s in a Keith Richards t-shirt with an oversized derby pushed back on her head. There’s opera on the PA system, Tchaikovski’s Eugene Onegin. At a tenor aria, her head drops back as if she’d just received an injection. The derby falls to the floor. And on her face, an exqusite pain. She’s wincing at the sublimity, its objective aesthetic beauty, and you’re thinking, this is the woman who sixteen hours earlier was bouncing around with a clarinet like a lunatic in an asylum, and you and five thousand others like you bounced around with her, the canals in your ears experiencing collective paroxysms. When the aria concludes and the orchestra subsides, you get up and retrieve Patti Smith’s hat. Her eyes remain closed, lost in the music. The eyes, lined with kohl, the nose just a bit too large for the narrow face, the perfect bow lips. Slowly the eyes open and they spot you standing alongside her. “Yeah, kid,” she says, “what?” You tell her she’s dropped her hat and you extend it. She says, “I didn’t drop it, man. I didn’t drop it. It fell. Weren’t you watching? Weren’t you listening? Didn’t you hear that fucking beauty?” You tell her you did. “Not if you’re policing peoples’ hats, man. Not if you’re policing peoples’ hats. Maybe I wanted that on the floor, at that moment, in that aria, and now you fucked it all up.” You sputter some attempt at an apology. “I can’t even understand you, man. Just give me the fucking hat.” A few minutes later, Patti Smith approaches your table. “Hey man.” “Ms Smith.” “Ah, so you know who I am. Getting to be a thing. Listen, something I gotta ask you.” “Please do.” “Please do? What are you like from the BBC, please do?” I blushed. “Nah, listen, like, back there, I was just fucking with you, man.” “Not a problem.” “Man, just listen, OK, let me finish.” “Please do.” “There’s that please do again. Listen, I feel bad if you got the wrong impression. See, I’m just…” You say it’s OK. “OK with you,” she says. “But what I keep trying to tell you is that it’s not OK”—and here she winds up like a pitcher, reaching way behind herself with her right hand, then coming forward like she’s throwing a fastball, but just at the point of release she spins the hand around and points a finger at herself—“with me, you dig?” You laugh. You tell her you dig. She says, “What, I say something funny? Now I’m making you laugh I’m funny?” You say, “I loved your show last night.” This stops the schtick. “You were there? Cool. What was your favorite song, and don’t tell me because the fucking night, I know you’re hipper than that.” “I liked the clarinet solo.” She beamed. “Dude.” She reached forward for a handshake with about sixteen parts. “How would you describe my playing?” You think for a moment, then say, “Kind of crypto-avant dada skronk.” She looks behind her. “Are we on like fucking candid camera, because that’s the most perfect—listen, what’s your name?” You tell her. “Clifford Foote,” she repeats. “With an ‘e’” you tell her. “Of course with an ‘e’, man,” she says. “Of course with an e. Otherwise it’s just a fucking foot. And what do you do Clifford Foote with an e. You must be like a poet or something.” “Film student.” “What I fucking say? So who’s your thing? Méliès? Cocteau?” “Cassavetes.” She says, “Cassa-- Hold on a second.” She goes to her table, scribbles something on her notepad and rips out the page. “Here,” she says. It reads

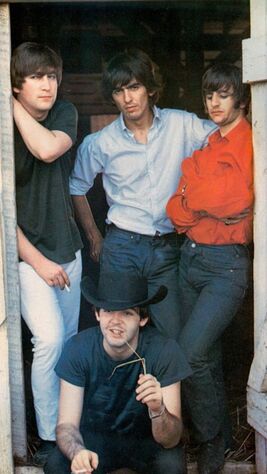

You spin it around on the table and she scribbles something that is the handwriting equivalent of her clarinet playing. “For life,” she says, “anywhere I’m playing, you get me?” Before you can ask her about taking the piss onstage, she’s at the turntable, selects Delibes’ Lakme, returns to her place at the window. At the exquisitely excruciating “Flower Duet,” her eyes squeeze shut, the neck goes slack, the derby floats to the floor. This time, you leave it there. ••• Her next show is uptown at Hurrah. You show security your pass for life. Security, big and bald with tattooed arms as thick as your legs, laughs in your face. Then Patti Smith moves to Detroit, the rest of your fucking life happens, and your girlfriend turns out to be right about at least one thing. TIM TOMLINSON was born in, and has returned to, Brooklyn, NY. In between, he's lived in Boston, New Orleans, Miami, the Bahamas, Shanghai, Florence, London, but mostly Manhattan. He's a high school dropout, a Columbia University graduate, and a co-founder of New York Writers Workshop. He teaches in NYU's Global Liberal Studies. Among his publications are Requiem for the Tree Fort I Set on Fire (poetry), and This is Not Happening to You (short fiction). His poems and stories have appeared in numerous US and international venues, including, most recently, Another Chicago Magazine, Teesta Journal, Quarterly Literary Review Singapore, and Telephone, a multi-media collaborative endeavor including arts from across the globe.  I enjoyed this interview. A member of the Berlin Philharmonic discusses his decision to leave (to leave!). Sadly, not too much dirt, but a lot to think about re career vs self. And always interesting to get a glimpse of life as a professional musician: The Berlin Philharmonic is one of the greatest orchestras in the world, playing with it a dream job for many young performers—including bassoonist Mor Biron. Growing up in a family of musicians in Rehovot, Israel (his father, Avner Biron, is the founder and music director of the chamber orchestra Israel Camerata Jerusalem), Mor Biron dreamed of playing with the Philharmonic, even if it was only for 12 seconds, “just to see how it feels.” After graduating from Jerusalem’s Academy for Music and Dance and Berlin’s Hanns Eisler Conservatory of Music, Biron received a scholarship from the orchestra’s apprenticeship program, the Karajan Academy, in 2004. After a stint as principal bassoon in Valencia, Biron joined the Berlin Philharmonic in 2007. His last performance as a member of the orchestra was on June 26, 2021 at its annual Waldbühne concert. I spoke with Biron about different perspectives of the orchestra—including arriving, departing, and the overabundance of masculine energy he encountered in between. VAN: Why did you decide to leave? Mor Biron: I felt the need to work and live in a way that aligned with my beliefs; I wanted experiences that I could grow with, that allowed for exploration. I want to keep making music, of course. But, in this orchestra, in this position, I felt like I had to make music in a certain way, one that—for me, at least—is no longer the right way. VAN:What is the right way for you? Mor Biron: I’d like to find a more feminine side of the artform—a softer, more delicate side. I want to work with people who are motivated by moving audiences, not by furthering their careers. Sure, I also wanted to have a career myself, and I got as far as I could. I’m grateful that I had the drive and energy for that and, as long as there’s something left of it, I’d like to put that energy towards other things now. VAN: Why were you not able to find that feminine side with the Philharmonic? Mor Biron: There’s a lot of masculine energy in the orchestra, which in turn is because there aren’t enough women in the orchestra. There aren’t enough feminine vibes in the individual sections. Recently, I went to a Philharmonic concert with my parents. For so many years, I watched and listened to the orchestra—onstage and off, in the concert hall and on the Digital Concert Hall. But this time, that lack of feminine energy hit me really hard. I saw this semicircle of men sitting there, and it didn’t matter what they did or how they played, all I saw was this male energy. I looked at my father and asked him, “Do you see it, too?” VAN: We know each other a bit personally through mutual friends. Whenever I saw you in the orchestra, either in concert or backstage afterwards, I got the sense that you didn’t really fit in. Was there any truth to that? Mor Biron: You’re not the first person to say that. [Laughs.] VAN: Was the decision to leave a process, or was there one decisive moment? Mor Biron: It was the kind of process where the decisive moment was instinctual. You’re running and running, and at some point you come to the cliff and you jump. The jump was quick—it only took a few minutes to write my resignation letter. But to arrive at that moment, that took me a few minutes plus my entire life. There wasn’t any long period of suffering or anything like that. In September 2019, I took a one-year sabbatical. I wanted to find out what “Mor minus the orchestra” was like, what was left of me. And, as it turned out, there was a lot. I was free to just do my thing. In the beginning, I barely played the bassoon. I traveled across Thailand. It was wonderful. When I came back from sabbatical last year, I wondered what could replace playing with the orchestra and applied for two professorships. But then I realized it was too soon—giving up one big thing and moving right into another. I knew I had to let go completely in order to make space for real change. VAN: How did your colleagues react? Mor Biron: I got a lot of compliments. I still get them today. Some say they’re proud of me, how brave my decision was.… All I did was write a letter. But we appreciate it when someone takes their life into their own hands, even though that isn’t the easiest road to take. Other colleagues didn’t really know how to deal with me or my decision. VAN: During the pandemic and resulting lockdowns, many freelance musicians were plagued by financial insecurity. You left a steady job. Mor Biron: I know. On the other hand, if I know that I don’t belong there anymore, that I don’t want to spend the rest of my life there, then I’d rather give that seat to someone who really wants to sit there. My story was that, from an early age, all I wanted was to play in this orchestra. My father is a conductor and founder of the Israel Camerata. I’ve been part of this world for as long as I can remember, all the concerts and recordings. Back then, there was a live broadcast every Thursday from the Philharmonie. When I was about nine years old, I watched the Berlin Philharmonic in concert with Abbado. I told my father, “I’d like to sit in this orchestra for 12 seconds, just once in my life. Just to see how it feels.” I could hear the difference between what came in through those television speakers and the other music around me. Well, be careful what you wish for: I wished for 12 seconds and got 17 years. [Laughs.] VAN: When did the dream start to fade? Mor Biron: I don’t see it as fading. There were evenings with the orchestra where I’d come home, complain about everything, and think, I can’t play there anymore. And then the next night, we’d have a concert that I’d thoroughly enjoy.… Which experience should I base my decision on? It took time, seeing these experiences come and go and repeat themselves, before I realized I couldn’t find any of the answers in my experiences–I had to find them in myself and make my own decision. When I was young, I struggled with making decisions, I never felt secure enough in them to swim against the tide, even if I knew it was right. Now, I have this security. VAN: Is it hard to grow old in an orchestra without it becoming routine, or without becoming cynical or bored? Mor Biron: You can just leave. No one will stop you. The stability, the financial security……the fear of losing equilibrium. For years, I’ve enjoyed leaning into awkward or embarrassing moments. That’s also why I love working with kids. VAN: You played under Simon Rattle as music director for 11 years. Now, Kirill Petrenko is ushering in a new era. That couldn’t change your mind? Mor Biron: No. Ten years ago, I had the chance to audition for a seat with the Israel Philharmonic. I remember thinking, “No, I won’t take the audition. I’m not finished with Berlin. I still want to learn a lot here.” Not many people are willing to take this kind of risk. Sometimes there are musicians who leave the orchestra to pursue a different career path, like former concertmaster Guy Braunstein. But even musicians with solo careers, like Andreas Ottensamer and Albrecht Mayer, usually stay in the orchestra. Because their solo careers wouldn’t have come close to what they are today without the orchestra. It’s the same for me. I arrange my own concerts now. I love soloing with and playing in orchestras, chamber music, jazz, improvisation. But I’m not looking for the next career. VAN: What were the highlights of your time with the Philharmonic? Were there any concerts with the perfect combination of conductor and composition? Mor Biron: One of the concerts where I can remember almost everything, as some say about playing Mahler 9 with Abbado, was “La Valse” with François-Xavier Roth. I’d never experienced something like that before, and will never experience anything like it again. The interpretation, the energy, the results… The orchestra was beaming. The musicians smiled as they played! He managed to break everyone out of their routines and set them free. Of course, it’s also nice to play the bassoon solo in “The Rite of Spring.” There was the “St. Matthew Passion” with Simon [Rattle], the Verdi Requiem with Muti. But then again, it’s Muti. How can you take him seriously? [Laughs.] VAN: You also play in the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra. What’s different about that? Mor Biron: Everything. It’s fun. We’re not just playing through our schedules.… Barenboim doesn’t exactly have a lot of feminine energy either. [Laughs.] But what I’ve learned from him is that playing in an orchestra means doing two fundamental things at the same time: listening and communicating. The better you are in both areas, the better you are as a musician and as a person. Barenboim was the first person to articulate this so clearly to me, 16 years ago in Pilas, near Seville. In any orchestra, not just mine, people don’t talk to you during your trial period. But they keep track of every mistake and, if you don’t get better: Ciao. VAN: You teach a lot, as well. Is there any advice you would give to students who are just starting out with an orchestra? Never forget that you didn’t get this job because they wanted you. You got this job because you wanted it. You offered yourself and they took you. You can always pack up and leave. It’s important for us to remember that we’re free to make any decision we want at any moment in our life. VAN: Where are you going next? Part of me wants to go back to Israel because of my family, my girlfriend, the sea, my grandmother… I moved away in 2004, when I was in my early 20s, and I’ve never lived there of my own volition. But it’s more important to wake up with a smile knowing that I’m exactly where I want to be. ¶ GET BACK My take after two episodes of Peter Jackson’s three-part Get Back documentary on the making of the Beatles’ Let It Be lp. A consideration of Episode 3 added ⅔ down column.

JOHN: diminished and dopey (in two senses of that term). His contributions are negligible. I was surprised to hear him equate his “Dig a Pony” to the level of Paul’s “Get Back.” Of course, that could be a power check, a defensive jab, but it’s also evidence of impaired judgment. And in the impaired judgment department: Yoko’s omnipresence. I’m a big fan of Yoko, a defender, and always was. This isn’t about who broke up the band, it’s about who belongs in the room, the laboratory. She adds nothing. Nothing. She subtracts much. It’s not just John’s judgment (which is nil) that I question here, it’s Yoko’s. How could she possibly justify inflicting herself on the band day after day after day? Didn’t she have anything to do? Where is her art? Where is her compassion for the others? She very clearly puts them off, and why should they accept it? But back to John: there are glimpses of the wit, the intellect, and glimpses of a tenderness, an elevated sense of compassion. And I think there’s evidence of a begrudging awe of Paul, whose talent has blossomed, and, at least at this moment, eclipsed the gifts of his great collaborator. Overall it’s a sad sight. When I think of John’s early dominance, how the ’63-’65 Beatles sound was so Lennon driven (“No Reply,” “I’ll Be Back,” “If I Fell,” “I Should Have Known Better,” “It Won’t Be Long,” “Norwegian Wood,” “Ticket to Ride,” “You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away,” and the super-abundance of A-side hits), it’s difficult to watch him flounder. On the whole, Let It Be is a weak, a very weak album, and inarguably the worst of the Beatles’ lot. Lennon’s contributions don’t help – “Don’t Let Me Down” and “Across the Universe” are good, but hardly top-shelf. Something has been lost, and it’s John. The drugs, the power shift within the band, the growing awareness that his one-time sidekick might actually be more of a musical talent than he: these are all factors. [I also think there’s a physical appearance factor: Lennon becoming more and more nerdy, a look that could only be appealing in the hippie era, whereas Paul cuts quite an appealing, quite a cosmopolitan figure. He’s not a parody or a comment on a look, or compensating for having no looks. He’s just, luckily, good looking, in the same mysterious way that he’s just so musically gifted.] PAUL: so present, so effortlessly musical, so professional. His sits at the piano, just going through some chords, some patterns, some improv exercises, are extraordinary. Watching his genius on display around the decidedly lesser, sometimes boorish, sometimes childish, always weaker expressions of his band mates, you have to wonder why he even bothers. I understand it as a profound love of the band, love for John, identification with “Beatles,” fear of change, and perhaps real sadness at watching his great mate descend. (In that sense, I’m reminded of Robbie Robertson watching the descent into debauchery and addiction of his once-equal Band-mates Rick, Richard, and Levon.) In terms of his output, his final contributions to the lp, obviously “Get Back” is the stand-out track. Watching its conception and evolution is a lesson in creativity, of first-thought-best-thought (like Lennon’s throwaway “Dig It”) going through the revision mill and coming out better. His seeking and acceptance of band mate contributions is generous, but probably unnecessary except perhaps to sustain the illusion of democracy (like a college dean and her faculty). “Let It Be,” too, has its place, but for me more b/c of Paul’s own poignant story (the loss of his mother Mary at an early age) than inherent value. It’s a B+ song from a guy who dreamed A+’s. But throughout the long five hours of the first two episodes, we see a musical talent so large, so multi-faceted, so uncontainable—he’s like Bachrach, Stevie Wonder, Brian Wilson without the mental illness. And the others are not. It’s really become as simple as that. SIDEBAR: These Assessments in Relation to Imminent Solo Output. Paul’s first record is an A-minus gem, with soaring high points (none quite as high as “Penny Lane” or “For No One,” but high, indelible). John’s “Cold Turkey,” while not a great song, is an important, honest song. It points to a pivot. “Instant Karma!” is a smash-hit A+ miracle, an anthem, a joy, a full-throated John in a kind of Godardian instant-song, proving that the black cloud over Let It Be had at least momentarily blown over. And then the Plastic Ono Band lp: searing, epic, A+. The ’63-’65 Lennon is back with a vengeance. Speaking of vengeance: George’s All Things Must Pass, a garbage dump of a box-set, partly saying, see what you all passed on? Some of it achieves A-minus levels: the title track, “My Sweet Lord,” although the Phil Spector production is more clutter than I’d like (the spare unaccompanied “All Things Must Pass” demo on the Anthology is, to my ear, much more effective). And Ringo: well, yeah, Ringo. Minor jukebox hits, instantly disposable AM radio ear candy, and that’s fine. Back to the film. GEORGE: not his finest hour. Not his finest seven hours. Petulant, moody, resentful. The perennial kid-brother, in awe at the big kids, with a growing awareness that maybe they’re the big kids because they’re bigger, and I’m not, no matter how hard I try, or will try. And a kind of giving up on trying, the sense that they don’t fully appreciate, they’re incapable of fully appreciating my contributions, so I’ll just give this much, take my paycheck, go home, and find satisfactions with other musical collaborators. His songs suck: “I Me Mine” and “For You Blue”—really? But they passed on others, and I don’t forget that this is the man who gave us a handful of the Beatles’ greatest songs: “Taxman,” “Within You and Without You” (an A+ for audacity if nothing else, the cojones to even imagine this as a possibility), “While My Guitar Gently Weeps,” even 1963’s “Don’t Bother Me,” and several of their enduring baubles: “I Need You,” “You Like Me Too Much,” “I Want to Tell You.” [Re “Something”: I prefer the Joe Cocker version; re “Here Comes the Sun”: I prefer the Richie Havens.] The George component reveals the fissures in the band, the egos and their limitations. It’s clear that John and Paul don’t think of his contributions as equal. Like dog biscuits, they toss Ringo a song here and there (Paul even says something like that while noodling at the piano in one of the sessions, not quite as crassly), and they give George space just a little less cavalierly. George is Fredo, and like Fredo, he doesn’t like it, but he finds it hard to protest. You get the sense that he’d be happier elsewhere, where he’s not treated like the kid brother, and that’s the sense that he’s been carrying, it appears, for at least a couple of years. He watches John and Paul, though, and especially Paul, at times like he just cannot believe the musical talent that pours forth. He’s a (begrudging) fan. RINGO: a strong case for luckiest man in the world. But luck has its cost, and here it looks like he pays a high premium. Nearly silent throughout, with a front-row seat to the efforts of his superiors. No wonder, I keep thinking, he went off and guzzled with Keith Moon. He’s a bit of a cipher, a bit of a session man. He offers next to nothing other than a reminder of the equilibrium they may once have had, and the love—which is the glue—that they all most certainly had and still have, although it’s been on a bit of a roller coaster since Brian Epstein died. Ringo is asked, “Did you like India?” He answers, “No.” Later, Paul talks about some of the Indian sojourn and footage of their time in Rishikesh appears. Paul mentions a moment when they’re walking along with the Maharishi and comments on John’s walk, his appearance: “It doesn’t even look like you.” That kind of intimate knowledge of his soul mate, that’s what makes these long hours so moving, and so worth it. Ringo is an electron with an awareness that he’s an electron and John and Paul are the nucleus. Or rather: John is a proton, Paul a neutron—they form the nucleus. George is an electron who wants to be in the nucleus. Ringo is an atomic particle. It looks like his awareness of being nothing more than an atomic particle weighs on him, but, in Ringo fashion, there’s an awareness as well that things could be worse. George, though, he’s not satisfied circling the nucleus. He wants to get in, but the nucleus is barely able to conceive of his dissatisfaction until it’s near or already too late. I look forward to the final episode, where finally the rooftop concert will appear. I wish that I could have high hopes for it as a triumphant event, but it can only get as good as the songs, and the songs, save for “Get Back,” just aren’t that great. (John, though, wow—he could actually play guitar. There are times when he seems as surprised, and delighted, by that as we are.) A Hard Night’s Day: After the Rooftop The first two episodes move laterally, from Twickenham to Apple, then vertically, from a ground floor to a basement (something of a return to origins for the Beatles, considering the training ground of the Cavern). The final episode makes the ascent to the roof. It’s a long wait for the climb—over five hours for the doors to close and the lift to rise—but it’s worth it. More than an hour of the final episode’s countdown is devoted to rehearsal, which involves jamming, riffing, clowning, revising, occasional discovery. Over the proceedings, the specter of Allen Klein, the specter of the imminent showdowns and official acrimony, hovers. But little Heather McCartney spinning around the wires and between the mikes and cymbals, the copious amounts of wine, and Billy Preston, help bring the temperature down and the camaraderie up. The playing gets tighter, the songs better. They plan a set-list, they’re anxious. Then they perform. For me, what’s delightful about the performance is how juiced up they become, and how well they play. The sound of the guitars, the athletic busy-ness of Paul’s bass, Ringo’s fills and punctuation—all truly fun and infectious. The Beatles on record sound so polished, so produced, and that’s probably a good, a necessary thing for a lot of the music. But their live sound, before the screams kill it, was so upbeat rock ‘n’ roll raw, and that’s what they loved (and what I love). The way they sound on Live at the Hollywood Bowl, in the footage from Shea Stadium, in the “Some Other Guy” black and white footage from the Cavern, when they all seem as plugged in as the instruments. What’s inescapable, though, is the limitations of the material they’ve worked up for this performance. I’m not sure why the decision was made to repeat “Get Back”—is it three times?—and to repeat “Don’t Let Me Down.” Wisely, they run through “Dig a Pony” once only. To me, that’s a lyric that strains for profundity, one of those “well he must be on to something because I don’t understand a word” songs, which is fine if the music works, and here it does, but only as well as it can. A grade B of a song that rises perhaps to B+ through effort and delight at live performance. They run through a good “One After 909,” but it’s telling that they have to reach so far back to come up with workable material. Overall, it’s a shame there wasn’t more time, it’s a shame it was so cold, it’s a shame they never had the chance to perform live again. The Stones had that three-year layoff, at least for US performance, and when they returned the excitement remained but the screaming had ended. The audience had grown up. Oh, what concerts the Beatles could have provided for the audience that they very largely created. (Something I do on occasion with my students: show them footage of the Beatles at Shea Stadium, 1965, where they seem to have arrived from the future and the audience looks like it’s still in the Eisenhower era; then, jump forward four years to the Woodstock documentary, where the magnitude of the generational transformation seems impossible. Must have been drugs in the water.) So the ending is bittersweet. They horse around a bit in the sound room, excited by the rooftop playback. They regroup the day after and work on the remaining material. As the credits roll, Peter Jackson does a good job with cutting between titles and footage. It’s worth it to stick around. Emotionally, it’s exhausting: what was, what could have been. I was left, and still am, in a Beatles fog. Their arrival transformed my life, transformed the music and the industry, transformed the US (or at least significantly informed the transformation). For four of five years their records, with an occasional lapse here and there (“Mr. Moonlight,” “Yellow Submarine”), were revelatory. By the White Album, which could have been trimmed to its advantage to one record*, the wear and tear and fissures were showing. And even they thought the Let It Be sessions yielded primarily crap. The tapes sat untouched until Lennon dumped them on Phil Spector’s lap with no instructions. So I don’t disparage the Beatles by agreeing with their own assessment. There’s a tendency to over-value their output that’s not commensurate with some of it. (The same thing is true, to a much greater—and, I think—damaging extent with Grateful Dead fanaticism. There, the fans don’t know music, they know, or practice, hero worship and idolatry, and they ignore 99% of the music out there.) If they’d ever had a chance for a reunion**, I can’t imagine any of the Let It Be sessions, excepting “Get Back,” would make the setlists. Maybe “Let It Be” since it’s so Paul identified, but he’s got over a dozen better songs. I listen to those, and John’s, and George’s still, and often. I love them. I remain an infatuated fan, with, perhaps, a bit of an oppositional ear. * Right off the bat I’d cut three George songs, keeping only “While My Guitar Gently Weeps”; the Ringo song (filler that deflates); “Wild Honey Pie,” “Rocky Racoon,” “Birthday,” and “Revolution #9,” all in a blink. That’s eight tracks, around thirty minutes of a 90+ minute package. Then what? The next round of cuts gets tougher, but I wouldn’t cry if we lost “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da,” or “Helter Skelter,” or “Sexy Sadie.” ** On particularly morbid nights, I play around with imagining Beatles reunion set lists. Mine would like this: 1. “Eleanor Rigby” (a cappella) 2. “Come Together” 3. “Taxman” 4. “Drive My Car” 5. “Ticket to Ride” 6. “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” 7. “With a Little Help from My Friends” 8. “Yesterday” 9. “Norwegian Wood” 10. “Something” 11. “Getting Better” 12. “I Should Have Known Better” 13. “Don’t Bother Me” 14. “Hey Jude” -intermission- 15. “Within You and Without You” (w/Indian accompaniment) Then it’s up for grabs. A dig back into the 63 and 64 vaults, maybe. A few big hits. A few Lennon covers (“Please Mr. Postman,” “Money”…) Last number (or last encore): “Good Night”? The latter part of the Abbey Road medley? I post this today in memory of one of my dearest friends, a man whose spirit and influence were so immense that they tended to obscure the very real demons he struggled with day to day. I met him in 1977, in the gym at Columbia University, where he tore around the 1/8 mile indoor track, in a beige cotton turtleneck and decidedly un-au-courant running shoes, as if fleeing from those demons. Other runners, fast runners, many of them twice Gary’s size, got out of his way. He’d been an undergraduate at the College, a philosophy major. Now he was an actor, and like so many artists in NYC, he worked whatever jobs he had to as he pursued his art. He was immensely talented, but tormented, gifted but burdened, and he came from a background that placed effort over expression, work over play, obligation over imagination. Every moment he took practicing guitar or memorizing Blake (he introduced me, through spontaneous recitation, to “What is the Price of Experience?”) must have been accompanied by self-doubt, by the question: what can I be doing for others right now, what tangible sacrifice should I be making? He got me my first job in NYC, working on moving trucks with other students, writers, actors, painters, musicians, drunks, addicts, scholars, and assorted scroungers of the NYC margins. Pound for pound, Gary was probably the strongest human I’ve ever met. He carried more weight—more book boxes!—on his unbreakable back than animals double his weight. In my mind’s eye, I see him bent at the waist ascending the staircase of some Lower East Side walk-up, with his fists gripping the ends of the burlap strap circling a stack of a half-dozen or more book boxes. In the summer, when we wore shorts to work, you could see the veins swelling in his calves, step by step, as he marched up the flights. And while you were still marveling at the will and the strength of his struggle, he’d be back down the flights with his strap at the truck, setting up another stack and saying he could probably take one, maybe two more boxes. His last couple of decades haven’t been easy, but he found a measure of joy, a measure of lightness, in the two brightest angels of his life, his beautiful and equally gifted wife and daughter, Christine and Clementine. Without them, he’d have had no reason to keep marching up flights. All of us who knew him and were touched by him--and you couldn't know him without being touched--are heartbroken at the news of his passing. I loved him like a brother. For me, he'll never stop being a guiding light.

A while ago, I wrote a story that was based on a story he told me--something that had happened to him in a counseling session with a psychoanalyst he really loved. It appears in my short story collection, the link to its original online publication appears to be down. I post it here in its entirety. Rest in peace, Gary McCleery. You've left an enormous mark, and an enormous hole that we have to get busy trying to fill, the way you would. The Motive for Metaphor What happened that day in his therapist’s office still surprised Maris years later, years after he’d left therapy, years after his therapist had died. Theo—he was on a first name basis with this therapist—Theo had asked him to bring a poem into a session, a poem he might want to talk about, a poem that, for some reason, it didn’t have to be clear, did something for him, “made him feel exposed” was how Theo put it, “made him feel wide open.” Maris brought two copies of Wallace Stevens’s “The Motive for Metaphor.” He’d expected to deconstruct it, like in a graduate school seminar, parse its lines, uncover its influences, expose its codes. Theo declined his copy, and asked instead for Maris to read the poem aloud. Maris hesitated. “I’ll feel like I’m at an audition,” he said. “It’s OK,” Theo told him. “You already have the part.” This was New York, Theo worked with numerous actors, he knew all about audition anxiety. Maris took a breath. He set his elbows on his knees. “You like it under the trees in autumn,” he began, and already he could feel something happening, his throat thickening, his pulse hammering. “Because everything is half dead.” There he came to a stop—he could hardly breathe. “I can’t,” he told Theo. His hands shook. “It’s OK,” Theo assured him, “it’s OK. Now continue, please.” And Maris tried. But something had a hold of him. It quickened, then robbed, his breath. He got through the first verse, he began the second. “You were happy in spring,” he read, “With the half colors of quarter-things.” And at “quarter-things” he stopped, at “quarter-things” it was as if he’d been slugged in the gut, in the solar plexus, and he doubled over in sobs that wracked his body, sobs he couldn’t control, that frightened him in their depth, that took his breath the way a sudden and long fall can, and you wonder not when you’ll get it back but if. And when it returns it’s a huge insucking gasp and you explode in sobs even more convulsively, even though you know that the sobs are sucking the water from the shoreline, as it were, the way a tsunami drains a bay. He saw Theo twice more after that, they never made any sense of the incident, at least not to Maris’s satisfaction. Then Maris left the country to make a film, his first shoot abroad, in Laos, a low-budget indie feature directed by a woman with a reputation in the margins of the business and a star who’d once actually been a star. He was gone longer than he’d expected—the shoot was a nightmare of mishaps that prolonged everyone’s stay well beyond their visas’ allowance. When finally they wrapped, Maris decided to travel, first into Cambodia, then Thailand. He’d left half his luggage behind in Vientiane, he couldn’t go back for it, it felt like he’d left half his life. It didn’t feel bad to lose half his life. He felt both lighter and nearer to destitute. Half his travel involved laundromats, or washerwomen beating his clothes. He started drinking again, beer at first, then local rice and palm wines as he sat on crates in a wife-beater, watching women with weathered skin wring out his soiled shirts. The wines aggravated his ulcer. One night in Bangkok, he helped a Swedish student who was getting mugged on a dark avenue alongside Lumpini Park. He traveled with her by train to Chiang Mai. They waited a week for visas to China. Her family was wealthy, she paid for everything, out of gratitude, she said. The Thai people were accustomed to seeing women like the Swedish student. But the Chinese stared at her as if they were seeing a vision, a visitation, a miracle. Some nights in bed, Maris looked at her that way, too—the length of her, the yellow radiance—in disbelief. He’d reached a point in his deterioration—a hardening of the destitution he’d cultivated for two decades—that elicited sympathy from beautiful young women. They found him intriguing, romantic, woebegone. He was a cross between Tom Waits and Gary Cooper. Since leaving America, he’d punched two new holes in his belt, and still his trousers sagged. He spent his first two weeks back in New York staring at the phone. He’d wanted to call Theo to say, let’s just have coffee or something, he’d wanted to say he was fine, that he was beyond therapy. But he knew he wasn’t, even if he didn’t know why. It wasn’t as if he heard voices, or stared into the void, say, of his refrigerator, which he used as shelving for scripts. It was just this gnawing anxiety, and the burning of his ulcer that kept him always within ninety seconds of a toilet. It was autumn, everything half-dead. He received a card from the Swedish student. She wrote of rhapsodies under the stars that night on the Yellow Mountain, he had to struggle to come up with her name. She’d become a quarter-thing. When at last he called, he was told of Theo’s passing. “Of AIDS?” Maris repeated, stunned. “Complications similar to,” the receptionist said, “but no one knows…” Maris said, “Theo was gay?” But he hung up even as the receptionist explained something that he couldn’t hear. It was immaterial. It was all immaterial. He took a job as an understudy in an O’Neill play. He could always rely on something drunken or Irish. He renewed his guitar playing, restored the calluses on his fingertips. He thought about how much he’d loved Theo, how Theo had saved his life without writing a single prescription. He wondered what it meant to love a man so much. And was it reciprocated? Theo was actually younger than Maris by about three years—he found that out after Theo’s passing. All along he’d thought Theo was at least ten years older. Choices can age you, Maris thought. Choices and responsibilities, two things Maris had scrupulously avoided. One day he was playing guitar on a bench in Tompkins Square Park. “Rex’s Blues.” A red-haired woman approached him. “That’s Townes Van Zandt you’re playing, isn’t it?” She had an Irish accent. Six weeks later he moved to Los Angeles where the red-haired woman belonged to a repertory company that welcomed Maris. The New York edge, they told him, that’s what they’d been missing. Maris told them he was from Montana, which was half true, but he didn’t remember which half. You reach an age, he told them, when the lies become the truth and the truth, it never mattered anyway, at least not as much as you thought it did. Unofficially, he became the company’s artistic director. The young actors wanted to know what he knew, which, they believed, was quite a lot. He told them about “The Motive for Metaphor,” and on the basis of his story, the company scribe wrote up a one-act with the same title. It ran for six weeks to capacity houses and critical acclaim. Maris directed himself. One night, he saw the Swedish student in the audience. On another, he could have sworn he saw Theo. He remained in character until he believed he didn’t have another tear left in him for as long as he’d live. |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed