|

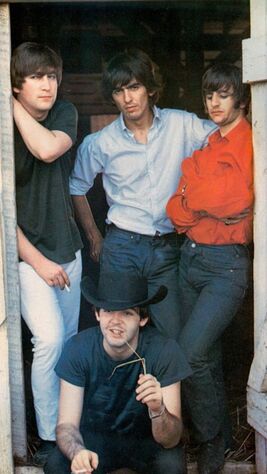

GET BACK My take after two episodes of Peter Jackson’s three-part Get Back documentary on the making of the Beatles’ Let It Be lp. A consideration of Episode 3 added ⅔ down column.

JOHN: diminished and dopey (in two senses of that term). His contributions are negligible. I was surprised to hear him equate his “Dig a Pony” to the level of Paul’s “Get Back.” Of course, that could be a power check, a defensive jab, but it’s also evidence of impaired judgment. And in the impaired judgment department: Yoko’s omnipresence. I’m a big fan of Yoko, a defender, and always was. This isn’t about who broke up the band, it’s about who belongs in the room, the laboratory. She adds nothing. Nothing. She subtracts much. It’s not just John’s judgment (which is nil) that I question here, it’s Yoko’s. How could she possibly justify inflicting herself on the band day after day after day? Didn’t she have anything to do? Where is her art? Where is her compassion for the others? She very clearly puts them off, and why should they accept it? But back to John: there are glimpses of the wit, the intellect, and glimpses of a tenderness, an elevated sense of compassion. And I think there’s evidence of a begrudging awe of Paul, whose talent has blossomed, and, at least at this moment, eclipsed the gifts of his great collaborator. Overall it’s a sad sight. When I think of John’s early dominance, how the ’63-’65 Beatles sound was so Lennon driven (“No Reply,” “I’ll Be Back,” “If I Fell,” “I Should Have Known Better,” “It Won’t Be Long,” “Norwegian Wood,” “Ticket to Ride,” “You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away,” and the super-abundance of A-side hits), it’s difficult to watch him flounder. On the whole, Let It Be is a weak, a very weak album, and inarguably the worst of the Beatles’ lot. Lennon’s contributions don’t help – “Don’t Let Me Down” and “Across the Universe” are good, but hardly top-shelf. Something has been lost, and it’s John. The drugs, the power shift within the band, the growing awareness that his one-time sidekick might actually be more of a musical talent than he: these are all factors. [I also think there’s a physical appearance factor: Lennon becoming more and more nerdy, a look that could only be appealing in the hippie era, whereas Paul cuts quite an appealing, quite a cosmopolitan figure. He’s not a parody or a comment on a look, or compensating for having no looks. He’s just, luckily, good looking, in the same mysterious way that he’s just so musically gifted.] PAUL: so present, so effortlessly musical, so professional. His sits at the piano, just going through some chords, some patterns, some improv exercises, are extraordinary. Watching his genius on display around the decidedly lesser, sometimes boorish, sometimes childish, always weaker expressions of his band mates, you have to wonder why he even bothers. I understand it as a profound love of the band, love for John, identification with “Beatles,” fear of change, and perhaps real sadness at watching his great mate descend. (In that sense, I’m reminded of Robbie Robertson watching the descent into debauchery and addiction of his once-equal Band-mates Rick, Richard, and Levon.) In terms of his output, his final contributions to the lp, obviously “Get Back” is the stand-out track. Watching its conception and evolution is a lesson in creativity, of first-thought-best-thought (like Lennon’s throwaway “Dig It”) going through the revision mill and coming out better. His seeking and acceptance of band mate contributions is generous, but probably unnecessary except perhaps to sustain the illusion of democracy (like a college dean and her faculty). “Let It Be,” too, has its place, but for me more b/c of Paul’s own poignant story (the loss of his mother Mary at an early age) than inherent value. It’s a B+ song from a guy who dreamed A+’s. But throughout the long five hours of the first two episodes, we see a musical talent so large, so multi-faceted, so uncontainable—he’s like Bachrach, Stevie Wonder, Brian Wilson without the mental illness. And the others are not. It’s really become as simple as that. SIDEBAR: These Assessments in Relation to Imminent Solo Output. Paul’s first record is an A-minus gem, with soaring high points (none quite as high as “Penny Lane” or “For No One,” but high, indelible). John’s “Cold Turkey,” while not a great song, is an important, honest song. It points to a pivot. “Instant Karma!” is a smash-hit A+ miracle, an anthem, a joy, a full-throated John in a kind of Godardian instant-song, proving that the black cloud over Let It Be had at least momentarily blown over. And then the Plastic Ono Band lp: searing, epic, A+. The ’63-’65 Lennon is back with a vengeance. Speaking of vengeance: George’s All Things Must Pass, a garbage dump of a box-set, partly saying, see what you all passed on? Some of it achieves A-minus levels: the title track, “My Sweet Lord,” although the Phil Spector production is more clutter than I’d like (the spare unaccompanied “All Things Must Pass” demo on the Anthology is, to my ear, much more effective). And Ringo: well, yeah, Ringo. Minor jukebox hits, instantly disposable AM radio ear candy, and that’s fine. Back to the film. GEORGE: not his finest hour. Not his finest seven hours. Petulant, moody, resentful. The perennial kid-brother, in awe at the big kids, with a growing awareness that maybe they’re the big kids because they’re bigger, and I’m not, no matter how hard I try, or will try. And a kind of giving up on trying, the sense that they don’t fully appreciate, they’re incapable of fully appreciating my contributions, so I’ll just give this much, take my paycheck, go home, and find satisfactions with other musical collaborators. His songs suck: “I Me Mine” and “For You Blue”—really? But they passed on others, and I don’t forget that this is the man who gave us a handful of the Beatles’ greatest songs: “Taxman,” “Within You and Without You” (an A+ for audacity if nothing else, the cojones to even imagine this as a possibility), “While My Guitar Gently Weeps,” even 1963’s “Don’t Bother Me,” and several of their enduring baubles: “I Need You,” “You Like Me Too Much,” “I Want to Tell You.” [Re “Something”: I prefer the Joe Cocker version; re “Here Comes the Sun”: I prefer the Richie Havens.] The George component reveals the fissures in the band, the egos and their limitations. It’s clear that John and Paul don’t think of his contributions as equal. Like dog biscuits, they toss Ringo a song here and there (Paul even says something like that while noodling at the piano in one of the sessions, not quite as crassly), and they give George space just a little less cavalierly. George is Fredo, and like Fredo, he doesn’t like it, but he finds it hard to protest. You get the sense that he’d be happier elsewhere, where he’s not treated like the kid brother, and that’s the sense that he’s been carrying, it appears, for at least a couple of years. He watches John and Paul, though, and especially Paul, at times like he just cannot believe the musical talent that pours forth. He’s a (begrudging) fan. RINGO: a strong case for luckiest man in the world. But luck has its cost, and here it looks like he pays a high premium. Nearly silent throughout, with a front-row seat to the efforts of his superiors. No wonder, I keep thinking, he went off and guzzled with Keith Moon. He’s a bit of a cipher, a bit of a session man. He offers next to nothing other than a reminder of the equilibrium they may once have had, and the love—which is the glue—that they all most certainly had and still have, although it’s been on a bit of a roller coaster since Brian Epstein died. Ringo is asked, “Did you like India?” He answers, “No.” Later, Paul talks about some of the Indian sojourn and footage of their time in Rishikesh appears. Paul mentions a moment when they’re walking along with the Maharishi and comments on John’s walk, his appearance: “It doesn’t even look like you.” That kind of intimate knowledge of his soul mate, that’s what makes these long hours so moving, and so worth it. Ringo is an electron with an awareness that he’s an electron and John and Paul are the nucleus. Or rather: John is a proton, Paul a neutron—they form the nucleus. George is an electron who wants to be in the nucleus. Ringo is an atomic particle. It looks like his awareness of being nothing more than an atomic particle weighs on him, but, in Ringo fashion, there’s an awareness as well that things could be worse. George, though, he’s not satisfied circling the nucleus. He wants to get in, but the nucleus is barely able to conceive of his dissatisfaction until it’s near or already too late. I look forward to the final episode, where finally the rooftop concert will appear. I wish that I could have high hopes for it as a triumphant event, but it can only get as good as the songs, and the songs, save for “Get Back,” just aren’t that great. (John, though, wow—he could actually play guitar. There are times when he seems as surprised, and delighted, by that as we are.) A Hard Night’s Day: After the Rooftop The first two episodes move laterally, from Twickenham to Apple, then vertically, from a ground floor to a basement (something of a return to origins for the Beatles, considering the training ground of the Cavern). The final episode makes the ascent to the roof. It’s a long wait for the climb—over five hours for the doors to close and the lift to rise—but it’s worth it. More than an hour of the final episode’s countdown is devoted to rehearsal, which involves jamming, riffing, clowning, revising, occasional discovery. Over the proceedings, the specter of Allen Klein, the specter of the imminent showdowns and official acrimony, hovers. But little Heather McCartney spinning around the wires and between the mikes and cymbals, the copious amounts of wine, and Billy Preston, help bring the temperature down and the camaraderie up. The playing gets tighter, the songs better. They plan a set-list, they’re anxious. Then they perform. For me, what’s delightful about the performance is how juiced up they become, and how well they play. The sound of the guitars, the athletic busy-ness of Paul’s bass, Ringo’s fills and punctuation—all truly fun and infectious. The Beatles on record sound so polished, so produced, and that’s probably a good, a necessary thing for a lot of the music. But their live sound, before the screams kill it, was so upbeat rock ‘n’ roll raw, and that’s what they loved (and what I love). The way they sound on Live at the Hollywood Bowl, in the footage from Shea Stadium, in the “Some Other Guy” black and white footage from the Cavern, when they all seem as plugged in as the instruments. What’s inescapable, though, is the limitations of the material they’ve worked up for this performance. I’m not sure why the decision was made to repeat “Get Back”—is it three times?—and to repeat “Don’t Let Me Down.” Wisely, they run through “Dig a Pony” once only. To me, that’s a lyric that strains for profundity, one of those “well he must be on to something because I don’t understand a word” songs, which is fine if the music works, and here it does, but only as well as it can. A grade B of a song that rises perhaps to B+ through effort and delight at live performance. They run through a good “One After 909,” but it’s telling that they have to reach so far back to come up with workable material. Overall, it’s a shame there wasn’t more time, it’s a shame it was so cold, it’s a shame they never had the chance to perform live again. The Stones had that three-year layoff, at least for US performance, and when they returned the excitement remained but the screaming had ended. The audience had grown up. Oh, what concerts the Beatles could have provided for the audience that they very largely created. (Something I do on occasion with my students: show them footage of the Beatles at Shea Stadium, 1965, where they seem to have arrived from the future and the audience looks like it’s still in the Eisenhower era; then, jump forward four years to the Woodstock documentary, where the magnitude of the generational transformation seems impossible. Must have been drugs in the water.) So the ending is bittersweet. They horse around a bit in the sound room, excited by the rooftop playback. They regroup the day after and work on the remaining material. As the credits roll, Peter Jackson does a good job with cutting between titles and footage. It’s worth it to stick around. Emotionally, it’s exhausting: what was, what could have been. I was left, and still am, in a Beatles fog. Their arrival transformed my life, transformed the music and the industry, transformed the US (or at least significantly informed the transformation). For four of five years their records, with an occasional lapse here and there (“Mr. Moonlight,” “Yellow Submarine”), were revelatory. By the White Album, which could have been trimmed to its advantage to one record*, the wear and tear and fissures were showing. And even they thought the Let It Be sessions yielded primarily crap. The tapes sat untouched until Lennon dumped them on Phil Spector’s lap with no instructions. So I don’t disparage the Beatles by agreeing with their own assessment. There’s a tendency to over-value their output that’s not commensurate with some of it. (The same thing is true, to a much greater—and, I think—damaging extent with Grateful Dead fanaticism. There, the fans don’t know music, they know, or practice, hero worship and idolatry, and they ignore 99% of the music out there.) If they’d ever had a chance for a reunion**, I can’t imagine any of the Let It Be sessions, excepting “Get Back,” would make the setlists. Maybe “Let It Be” since it’s so Paul identified, but he’s got over a dozen better songs. I listen to those, and John’s, and George’s still, and often. I love them. I remain an infatuated fan, with, perhaps, a bit of an oppositional ear. * Right off the bat I’d cut three George songs, keeping only “While My Guitar Gently Weeps”; the Ringo song (filler that deflates); “Wild Honey Pie,” “Rocky Racoon,” “Birthday,” and “Revolution #9,” all in a blink. That’s eight tracks, around thirty minutes of a 90+ minute package. Then what? The next round of cuts gets tougher, but I wouldn’t cry if we lost “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da,” or “Helter Skelter,” or “Sexy Sadie.” ** On particularly morbid nights, I play around with imagining Beatles reunion set lists. Mine would like this: 1. “Eleanor Rigby” (a cappella) 2. “Come Together” 3. “Taxman” 4. “Drive My Car” 5. “Ticket to Ride” 6. “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” 7. “With a Little Help from My Friends” 8. “Yesterday” 9. “Norwegian Wood” 10. “Something” 11. “Getting Better” 12. “I Should Have Known Better” 13. “Don’t Bother Me” 14. “Hey Jude” -intermission- 15. “Within You and Without You” (w/Indian accompaniment) Then it’s up for grabs. A dig back into the 63 and 64 vaults, maybe. A few big hits. A few Lennon covers (“Please Mr. Postman,” “Money”…) Last number (or last encore): “Good Night”? The latter part of the Abbey Road medley?

2 Comments

Doug Edwards

12/11/2021 06:59:10 pm

A definite review if ever there was one. Very pointed and insightful Tim, I agree with most everything written. You've identified many of my flighting thoughts through the decades since. Paul was always my favorite Beatle of course we each had one, Chuck was Ringo. lol Bravo Timmy! ;-)

Reply

Doug Edwards

12/12/2021 07:17:38 am

Fleeting not flighting. 🙃

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed